| Algae | Crustaceans (cont’d) |

| ?Jania sp. | Atergatus floridus – type of mud crab |

| Udotea flabellum | Squilla sp. (order Stomatopoda) |

| Halimeda opuntia | Echinoderms |

| Caulerpa taxifola | Arachnoides placenta – sand dollar |

| Angiosperms | brittle star (order Ophiuroidea) |

| Halodule uninervis sea grass | Gastropods |

| Halophila ovalis sea grass | Polinices conicus |

| Halophila spinulosa sea grass | Polinices mammatus |

| Bivalves | Nassarius dorsatus |

| Anadora pilula – pill ark | Nassarius pullus |

| Pinna bicolor – razor clam | Nassarius luridus |

| Mactra sp. | Nassarius graphiterus |

| Tellina sp. | Planaxis sp.- cluster winks |

| Trisidus tortuosa – ark or twisted ark | Bursatella leachii – sea hare |

| Placamen sp. | Stylocheilus striatus – sea hare |

| Malleus alba – hammer oyster | Hemichordates |

| Placuna placenta – window pane shell | Ptychodera flava – an acorn worm |

| Crustaceans | Polychaetes |

| Portunus pelagicus – blue swimmer crab | Diopatra sp. – an annelid worm |

| Charybdis sp. – a swimmer crab | Anthozoans |

| Matuta sp – ’moon crab’ | Actinoporis elongatus – sea anemone |

| Scopimera inflata – sand bubbler crab | Cryptodendrum adhaesivium – ditto |

| Clibinarius sp. – a hermit crab | Brachiopods |

| Diogenes avarus – a hermit crab | Lingula sp. (L. anatina?) |

The species list above was compiled from John’s observations at the site and his examination of some of the many photographs submitted (thank you Jo, Julia, Margaret and Melissa!). The comments below are also mostly based on John’s extensive knowledge, augmented by a few garnerings of my own. I take full responsibility for errors and if you spot any please let me know.

The general write-up of the trip, Shelly Cove-Treasure Trove!, can be read here.

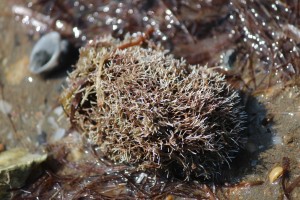

Algae: The first three listed are all calcareous algae. Jania sp. is a red alga of which we found the calcareous skeleton. U. flabellum and H.opuntia, both green algae, are also calcareous and, when they break down, contribute organic material to the sand. Caulerpa taxifola, native to the Indian Ocean, is regarded in some places as highly invasive, probably due to its popularity as an aquarium plant although it has been recorded from the Townsville area since the early 1970s. We also found a frond of Turbinaria ornata, not listed above because it would have drifted in from a rocky or coral reef elsewhere. According to John, it is the sort of material that gathers in the stingray pits, is gradually buried in the sand, eventually becoming mineralised and releasing its nutrients back into the sea.

Angiosperms: John found three of the four species that occur in this area. H.uninervis is the most grass-like in appearance with long narrow leaves, H. ovalis (“paddle weed” or “spoon grass”) has oval leaves and H.spinulosa has a fern-like appearance. Do please visit this Seagrass Watch site [Link expired] to learn more about the importance of seagrass – there is a great little 4 minute video which (I promise) will astound you!!

Bivalves: Pinna bicolor (razor clam), found round most of the Australian coast, is edible. The dead shells of the hammer oyster (Malleus alba) may also be found. The very thin bivalve, Placuna placenta, is called a “window pane” shell because of its almost transparent nature – we only found the shell of this, not the live animal.

Crustaceans: Scopimera inflata is the crab that rolls the sand into little balls that spread out around its burrow. Portunus, Charybdis and Matuta species are all swimmer crabs. Portunus and Charybdis species can be distinguished from each other by the number of lateral spines, Portunus having nine, and Charybdis six. The blue swimmer, P. pelagicus is popular with seafood lovers. The stomatopod (aka mantis shrimp), which was responsible for the conspicuous entrance and exit burrows in the sand, is believed to be a squillid that spears its prey with spiny, barbed appendages.

Gastropods: Nassarius species, often called dog whelks, are scavengers feeding on freshly dead or moribund animals. John describes how they locate prey by waving a long inhalant siphon from side to side as they walk and can sense bio-chemicals released from damaged cells at very low concentrations. They compare the odour on each side of the swing and will eventually locate the prey by turning towards the highest concentration.

Polinices species are also called moon snails. John has given a graphic account of their predatory behavior: “The snail moves along just under the surface of the sand and locates the prey by touch or vibration. When the prey (bivalve) is secured it will burrow a little deeper, and quietly drill a hole, using a pair of rasping jaws and the tongue-like rasping radula. To keep the victim quiescent it slobbers a mucus containing a narcotic onto its prey. The small hole is just large enough for the Polinices to insert its proboscis and radula and start feeding on the bivalve flesh. When the bivalve gapes open the snail will consume the partly digested flesh.” Hmm, one can only hope the narcotic effects are pleasant!

Strictly speaking the Planaxis (cluster winks) are out of place on this list because they are dwellers of rocky not sandy shores, but since they were the first species we spotted when we got to the beach it seems churlish to omit them. They are one of the few tropical gastropods that broods its embryos inside the shell before releasing them into the sea as larvae.

The two sea hare species attracted a lot of attention. Unlike most gastropods they have an internal shell. B. leachii, also called the ragged or woolly sea hare, was the shaggier of the two with very distinctive blue spots. S. striatus is smoother with a linear streaky pattern. Both will release a purplish ink as a defence mechanism and both feed on blue-green algae which form an epiphytic cover on old seagrass.

Anthozoans: Not all sea anemones attach themselves to rocks. Two species were found that partially conceal themselves in the sand. C. adhaesivium, which can grow up to 30cm, gets its species name from its sticky tentacles. A. elongatus squirts out sprays of water when disturbed.

Brachiopods: The species we found at Shelly Cove (and also at Geoffrey Bay is 2014) is probably L. anatina. Lingula have often been described as “living fossils” and, though this may not be strictly true, brachiopods of the same or very similar form have existed since as far back as the Cambrian period (approx 500 million years ago). They live in a vertical burrow, with the shell that encloses most of the body, at the top.

For those wondering if we ever lifted our eyes above ankle level – yes, we admired the sea eagle and brahminy kite that overflew us and the red-backed wren that perched on a leafless twig beside the track. Melissa took photos of the native kapok flowers and seed pods (Cochlospermum gillivraei) and the colourful seed pods of the peanut tree (Sterculia quadrifida) and Julia photographed the bright red fruit of the native cherry (Exocarpos latifolius). See the file of collected photos here and don’t forget the overall report of the trip Shelly Cove – Treasure Trove, available here.